by Matt Pulle

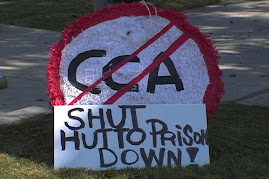

Located in a bland, almost anonymous Green Hills office park of fake lakes and fountains is the headquarters of the nation's largest private prison company, which, at the moment, may be the most disparaged corporation in the country. Since its inception in 1983, CCA has encountered legions of angry detractors who believe that the business of punishing criminals should not be—well, a business. But if the company has become accustomed to criticism over the years—like a best-selling author whose novels garner predictably bad reviews—it is now mired in a series of scandals, embarrassments and public-relations catastrophes that may tar its reputation for years to come.

In the last 18 months alone, CCA has been the target of several stinging lawsuits supported by detailed affidavits and third-party reports alleging dangerous and inhumane practices that have put inmates' lives at risk. Whistle blowers, once in positions of trust at CCA, have emerged from the shadows to tell vivid tales of corporate misconduct. Federal authorities have castigated the publicly traded corporation for operating an immigration detention facility in Texas on the cheap. And at that CCA complex—which at one point forced children of immigrant detainees to dress in prison garb—dozens of incarcerated women and children have come forward with gut-wrenching tales of anguish and neglect.

...In 2005, Michael Chertoff, secretary of the Department of Homeland Security, which runs the Immigration and Customs Enforcement Division (ICE), ended the practice of "catch-and-release"—which permitted undocumented immigrants like Elsa to remain free at-large while they awaited their day in court. Under catch-and-release, no-shows were common. So after 9/11, the specter of illegal immigrants from all over the world roaming the country became a security issue. Pilot programs sprung up that tracked immigrants with electronic bracelets, though Chertoff went with a draconian plan instead: Throw many of these men, women and children in Hutto, a former medium-security prison that was surrounded by a 15-foot fence topped with rings of barbed wire when it reopened in 2006 as a place for immigrant families.

...Just about every affidavit from a child or mother portrayed Hutto the same way—as a rough and cold place, where kids lie awake at night hungry and crying in the dark. And if they act up, like children often do, a guard would threaten to remove them from their families. To hear the stories from inside the walls, Hutto seems more like a medieval dungeon than a 21st century facility run by a wealthy company.

"The conditions were shocking," says Barbara Hines, a University of Texas law professor who spent many hours inside the facility representing detainees. "There were children in prison garb dressed like their parents; it was like an adult prison system. Seven times a day parents and their children were required to stay in their pods so they could be counted. Laser beams shined through the cells at night."

Just about everyone else who walked through the gates at Hutto, including federal authorities, saw it as a deeply troubling facility. In March 2007, ICE inspectors visited Hutto and, in their own distinct bureaucratic language, corroborated the anguished accounts of the detainees. The inspectors noted that their "overall review of the facility can be accurately rated as deficient" and determined that the staff wasn't following basic standards of detention.

"The Review Team's observation of CCA's overall attitude is of disinterest and complacency in their work performance," the agency noted in its report.

A month later, an interoffice memo from ICE said that at Hutto, CCA is "losing staff as quick as they can hire them." That's because the company was only paying its detention officers around $10 an hour, nearly $4 less than what they could make at the county jail.

"As long as CCA continues to hire employees at this rate per hour, they will continue to experience the problems they are currently experiencing on the floor," read the memo. "The current problems CCA is experiencing are a direct result of what 'they are paying their employees for.' Unfortunately, it is at ICE's expense."

Among other issues, the Scene asked CCA to address the portrayal of Hutto that emerges from both federal officials and the people who lived there. The company declined to comment on any and all matters in this story, instead emailing news clips and a U.S. magistrate's report of the facility. That report, which came three months after the ACLU filed its federal lawsuit, depicted a more humane place than other earlier accounts and noted, "there have been attempts to 'soften' the feel of the building." The magistrate observed that the staff removed door locks and hung murals on the walls, "although the building still retains a very institutional feel."

...By all accounts, Hutto is no longer as oppressive as it was when Elsa and her family first arrived from Honduras. But why didn't CCA get it right from the start? Or to put it more bluntly, why did a rich company—one with $388 million in revenues last quarter—have to be told by the ACLU to cease treating innocent children like criminals?

"The point I'd like to make is that none of these changes were done voluntarily," says Hines, the attorney. "When you look at CCA and ICE, the question is, how would this facility have been if no one found out about it?"