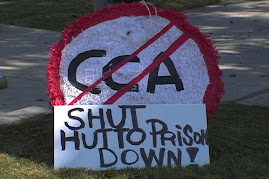

The New Yorker feature A Reporter At Large this week has what may be one of the most comprehensive articles on the T Don Hutto facility and the national issue of family detention. Reporter Margaret Talbot's article "The Lost Children" includes discussions of immigrant detention, the role of corporations in lobbying for greater incarceration, the impact of detention on children, and some of the chronology of Hutto's evolution.

The complete article is available free on their website. In the meantime, some highlights from the abstract include:

Hutto is one of two immigrant-detention facilities in America that house families—the other is in Berks County, Pennsylvania—and is the only one owned and run by a private prison company. The detention of immigrants is the fastest-growing form of incarceration in this country, and, with the support of the Bush Administration, it is becoming a lucrative business. At the end of 2006, some fourteen thousand people were in government custody for immigration-law violations, in a patchwork of detention arrangements, including space rented out by hundreds of local and state jails, and seven freestanding facilities run by private contractors.

Last August, the A.C.L.U. settled its suit against the government. The agreement entails a number of changes at Hutto, including eliminating the head-count system, providing pajamas for children, letting kids keep a limited number of toys in their room during the day, making a priority of hiring people with experience in child welfare, and installing curtains around the toilets. In the months before the lawsuit was settled, Hutto had already started making changes: it got rid of the razor wire; expanded the length of educational instruction, first to four, then to seven hours a day; and began allowing detainees to wear their own clothes. Yet it seems unlikely that these changes would have been made without pressure from the A.C.L.U. lawsuit and from advocates like Barbara Hines and her students. The settlement also aimed to get people out of detention faster and stipulated that families at Hutto have their cases reviewed every thirty days, to determine if they could be released on parole or on bond.

It’s clear that Hutto is now a very different, and more humane, place than it was before the lawsuit. But, Gupta says, “it shouldn’t have taken the A.C.L.U. to make the government realize that holding innocent children in a converted medium-security adult prison is a bad idea.”

A separate internal memo, which was obtained by the A.C.L.U., expressed particular concern about the high turnover among employees at Hutto. The memo’s author, whose name is redacted, complains about how hard it was to get straight answers from C.C.A. about staffing. (“Approximately five requests were made.”) The memo goes on to report that, of the three hundred and thirty-eight employees who had been hired since Hutto opened, in May, 2006, two hundred and three had quit or been fired by March, 2007. That meant that “the average length of employment for the 170 critical positions of detention officer, program facilitator, correctional officer, and case manager is 3.01 months. C.C.A. is losing staff as quick as they can hire them.” The memo blames low pay—C.C.A. pays new employees $10.22 an hour, versus the county standard of $14.36. (In general, private prison companies pay considerably less than public prisons.) The memo continues, “Unfortunately, the caliber of some employees at the T. Don Hutto facility is not as high as it should be considering the nature of business that is required in managing a family residential detention facility.”

When we place families in a facility like Hutto, are we punishing them for coming to America? Or are we just keeping them somewhere safe, so that they don’t get separated or disappear while we figure out what to do with them? Or, rather, is our policy to try somehow to combine the practical and the punitive? After all, if the goal was simply to keep track of immigrants, in most cases an electronic monitoring bracelet would suffice. And if the goal was simply to keep families together, we could surely house them in something other than a former prison, in a place where employees are trained in child welfare and kids can get fresh air. The decision to house families in a former prison was, perhaps, not so arbitrary after all. At the meeting that day, Cynthia Long, one of the county commissioners, a woman in a businesslike red blazer and glasses, spoke about keeping families together. But she also said something that probably represented the gut feeling of a lot of people who are angry about illegal immigration. Long said, “The thing we forget is the adults who are being detained have broken the law.” Unfortunately, she went on, children sometimes “have to suffer with the sins of our parents”—“to suffer, if you can call it that, because of their parents’ choices.”

Click here to learn more about the history of T. Don Hutto.