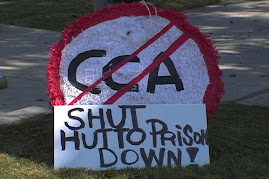

The alliance of attorneys, grassroots organizers, and a diverse coalition of outraged Texans from across the state has been getting some much-deserved kudos in the press. Check out this Austin-American Statesman article on how it all came together (and about how sometimes it didn't, which is okay, too). There were hundreds more involved than are mentioned by name-- if you're one of them, your hard work has been recognized!

T. Don Hutto detention center united diverse group in protest

Group's efforts helped lead to an overhaul of nation's immigrant detention policies.

By Juan Castillo

AMERICAN-STATESMAN STAFF

Thursday, August 13, 2009

When she first set foot in the T. Don Hutto immigrant detention center in Taylor shortly after it opened in 2006, Frances Valdez was not prepared for what she saw behind the former medium-security prison's razor-wire-ringed perimeter. There were children inside. Infants in prison-like uniforms, and pregnant women.

"It was shocking," Valdez said.

A recent graduate of the University of Texas School of Law, Valdez immediately called her mentor, Barbara Hines, the director of the school's immigration clinic where the young Austin lawyer was a clinical fellow.

"You're not going to believe this," Valdez told Hines — a bold assertion considering that with more than three decades of experience working on immigration law issues, Hines had probably seen it all.

But Valdez was right, Hines said

recently, recalling with still-heavy emotion the things she witnessed on her own visit to the Hutto center a week later that August.

"Just thinking about it takes me back to that place," Hines said. "It was so dire. It was the most depressed population I think I've ever seen."

Last week, three years and three months after the Hutto detention center opened, the Obama administration announced it will stop holding families there as it looks for alternatives to prison cells for some immigration law violators as part of an overhaul of the nation's immigration detention system.

The policy shift might not have been possible, according to some analysts, if not for the work of an unlikely but effective patchwork alliance of attorneys and community activists that emerged after Hines' and Valdez's unsettling initial visits to the Hutto center. The partnership quickly mushroomed to include hundreds, if not thousands, of people, including twenty-somethings and senior citizens, Williamson County residents, immigration reform advocates, human rights groups, documentary filmmakers, immigration clinic students and faculty and the American Civil Liberties Union. Though participants say they were not always on the same page, they were unified in their unrelenting calls for the government to close the center and to stop detaining families there.

They succeeded in drawing national and international media attention to the center as well as the scrutiny of international human rights groups. And in 2007, a lawsuit by the ACLU and Hines' UT law clinic led to a settlement agreement ordering the government to maintain improved conditions at the detention facility, about 30 miles northeast of Austin. (Set to expire later this month, the agreement was extended last week.)

"I think all of that (work by activists and attorneys) led to getting the new administration to understand that Hutto was an entirely inappropriate place to hold families," said Michelle Brané with the New York-based Women's Refugee Commission and author of its scathing 2007 report on family detention. "The reason they realized that is because we were able to inform them of what was going on there and explain why it was inappropriate."

Hines said the alliance was an "amazing experience" that showed how lawyers and activists, though sometimes at odds, could ultimately work together.

"Fundamentally, there was something about Hutto that really tugged at people's heartstrings," said Bob Libal with the grass-roots coalition Texans United for Families, which helped organize dozens of vigils and rallies outside the Hutto center's fences beginning in late 2006. "There were children there, and I think that makes people question the whole premise behind detention."

Detaining families

Those locked up at Hutto — in roughly 10-foot-by-10-foot cells — hail from all over the world and are seeking asylum or are being held on what the government defines as administrative, noncriminal violations of immigration law.

Only one other facility in the country — the Berks Family Shelter Care Facility in Leesport, Pa. — detains immigrant families. Those being detained in Taylor will be transferred by the end of the year to Berks, which will remain open pending further reforms, officials announced last week.

The decision to detain families was part of a 2006 Bush administration policy that ended a long-standing practice called "catch and release," under which immigrants promised to appear before a judge at a later date when there weren't enough beds to hold them.

Officials said mandatory detention was necessary because many families skipped their immigration hearings. They said detention was a safe, humane way to deal with families and keep them together.

But the Hutto center quickly came under fire amid a lengthy list of accusations of inhumane, substandard care and living conditions, among them that families were denied adequate diets, education, recreation, and medical and mental health care. Children initially received only one hour of education a day. Valdez and Hines said that in the beginning, parents were denied private meetings with counsel, meaning that many had to describe fleeing sexual abuse, imprisonment or torture in their home countries while in the presence of their young children.

Brané, who visited the center in December 2006, said parents told her that guards frequently threatened to separate them from their children if they didn't behave.

Amid the outcry, and as activists began steadily beating the drum for the center's closure, government officials expanded education and recreation and implemented other improvements early in 2007. But attorneys and activists continued arguing that imprisoning families, who in many cases were fleeing persecution in their home countries, was traumatic for the children and that there were plenty of alternatives to detention. Last week, government officials said they would consider alternatives, such as supervised release and the use of ankle bracelets, for some families.

Joining forces

Soon after the 2006 visits of Valdez and Hines, immigration law clinic students began providing representation to families held at the center.

Hines said they decided early on to enlist the help of activists to get the word out. By December 2006, community activists had helped organize the first of dozens of candlelight vigils at the center. Valdez said that even though only about 30 people attended the first vigil, "that's when it blew up." Soon, media representatives from around the world were calling about the lockup in Texas that held children and families, some for several months at a time. Refugee and human rights groups began descending on Taylor or monitoring developments there.

Valdez, who now practices immigration law in Houston, said that under their growing relationship, attorneys — the only ones who had access inside the center — typically described to activists the conditions and developments there. All used that information to consider their strategy in the campaign to close the center.

But the informal partnership was occasionally tinged with difficulty. Sometimes, activists wanted to know more than the attorneys could share because of attorney-client privilege, Hines said.

"We had to say, 'This is what I can tell you and you just have to trust me,' " Valdez recalled.

Activists had to learn to accept that while they were advocating a cause, attorneys were representing the best interests of their clients, said MaryEllen Kersch, a former Georgetown mayor who attended many of the vigils and organized a public forum on family detention. Kersch said that though she understood it was best for the plaintiffs, the settlement in the 2007 lawsuit that accused the government of violating the rights of minors at the center disappointed her.

"From a reformer's point of view, it sort of took the heat off the issue and gave what was being done (at Hutto) a little bit of a cover of acceptability," Kersch said.

She said diverse groups never lost sight of their overarching goal. "We all agreed on one thing: that T. Don Hutto needed to stop putting kids in prison."

jcastillo@statesman.com; 445-3635